Bingo Big

APRIL SUPER BINGO UPDATE 3/4/2021

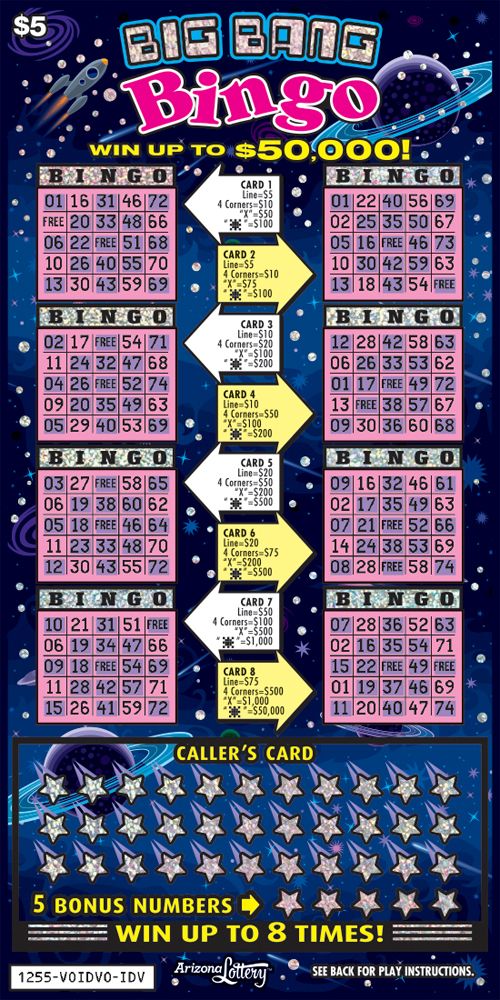

Big Tex Bingo offers a variety of bingo games every day of the week. To view a larger version of the game schedule for each day, click on each day below. Playing more bingo cards will increase your bets and your chance to win big! Next, select how many numbers you'd like to extract; this is the number of bingo numbers that will be randomly selected during the game. Next, place your bets, but keep in mind that you can only bet up to one dollar per number card. When you're ready, click play to start. Pack up for your adventure now with big win in 2018. Play with multiple cards, up to 8 each round and enjoy fantastic bingo rewards. The more cards you buy, the higher chance to call BINGO and WIN BIG! Even better are the various Power Ups that help boost your winning!

The April 5-7 Super Bingo event is officially SOLD OUT. Limited Waiting list spots are available for the April event.

If you would like to be placed on the list, please call the Super Bingo registration line or fill out the request form and select the April 5-7 (waiting list only) option for event.

What is Super Bingo?

Know More About This Captivating Game

Super Bingo is a large event that draws hundreds of people from all over the country to Downtown Las Vegas. For the players who come from as far away as Hawaii and Canada, Super Bingo is an opportunity to win big and socialize with like-minded bingo players.

Our $130,000 tournament features many fun-filled games of Bingo over 2 days and a super coverall both days. The Plaza Hotel Casino offers bingo only sessions for $130 or room-and-bingo packages that start at $239 for a three-night stay.

We offer an open bar during the sessions and play takes place in our remodeled ballroom. Come experience the largest bingo tournament in Downtown Las Vegas. Our upcoming schedule can be found below.

Super Bingo Recap

by Natasha Boas

The first-ever museum retrospective for Bernice Lee Bing (1936-1998) is a gem of a show: that rare small-scale retrospective that appears at the margins of the artworld but radiates and refracts in ways that a massive retrospective cannot. “Bingo” to her friends and colleagues, the artist has until now been an enigmatic footnote to the history of 20th-century art in the Bay Area, and Bingo: The Life and Times of Bernice Bing highlights the glaring omission of her work. Trained at the most prestigious art schools and exhibited alongside art-star peers, this Chinese-American lesbian artist remained outside of the popular narration of the Bay’s modernist cultural history until now. The O appended to her given surname resounds with the O of the outer fringes and counter-spaces she occupied throughout her life and career: other, outsider and outlier.

The exhibition, curated by Linda Keaton, the Sonoma Valley Museum of Art’s executive director, stands as a corrective to how little we have seen or heard of Bing’s work. It features 29 paintings and drawings and is accompanied by a mural/time-line that overlays Bing’s biography with the history of Bay Area art — a dramatic and surprising element that enables viewers to visualize the obvious omissions that mark Bing’s career. The catalog includes new scholarship by Susan Landauer and Jennifer Banta; it, along with a 35-minute documentary (The Worlds of

Bernice Bing, 2013) by Madeleine Lim, are both available for viewing in the galleries and extend the show’s art-historical footprint.

Other resonant Os define Bing’s fraught early life. Born in San Francisco’s Chinatown in 1936 of Southern Chinese descent, she and her sister were orphaned by 1941. When their mother died, the sisters were placed in a series of Caucasian foster homes, punctuated by stays in Oakland at their Chinese-born grandmother’s home, which connected them intermittently to a key source of cultural transmission. Thus began Bing’s marginalization. In 1957, the artist received a scholarship to attend California College of Arts and Crafts, and studied under Richard Diebenkorn and Saburo Hasegawa. From them, she learned technical painting skills, mental and spiritual strategies, and teachings that would influence her oeuvre throughout her life. In 1959, Bing moved to the California School of Fine Arts, which one year later would become the San Francisco Art Institute. Bing was part of the first master’s program in fine arts and was the first Asian-American woman to receive her MFA in 1961. At SFAI, Elmer Bischoff and Frank Lobdell were Bing’s primary painting professors, and they steeped their teaching in the academics of the Bay Area Figurative Movement and Bay Area Abstract Expressionism.

The influences of her art-school guidance, as well as the “roadmap” to understanding her future paintings, can be found in two paintings: Abstract Figure (c. 1960), revealing what she was doing in her early years and what was de rigueur in the San Francisco painting scene of the time, and A Lady and a Road (1960), a painting that stands as the exhibition’s centerpiece. The latter defines Bing’s best-known works and that part of her career that is best-documented, including in several Artforum articles that appeared in conjunction with her San Francisco exhibitions. This abstracted pink nude odalisque, rendered in a flat field of lines and colors, is

distantly reminiscent of a Diebenkorn tableau. It hovers between figuration and abstraction but is decidedly Bing’s own language, emphasizing the sensuous shapes of the female nude rendered with inimitable pink-and-yellow color juxtapositions and her signature black line, both of which make for a tense yet harmonious composition.

Bingo: The Life and Art of Bernice Bing proffers a view of artworld marginalization that arose from being an Asian-American lesbian artist coming up in the avant-garde world of the San Francisco Beat artists in North Beach—a milieu dominated by heteronormative-couple culture and the white male artists who were her classmates at SFAI. Jean and Bruce Conner, Manuel Neri and Joan Brown and Wally Hedrick and Jay DeFeo were some of the twosomes that defined the visual aesthetics of the Rat Bastards Protective Association, a group living and working in the building at 2322 Fillmore St. in San Francisco that become known as

Painterland. Bing accompanied artist Joan Brown on a trip to view Brown’s exhibition at the Staempfli Gallery in New York in 1960, where she came into direct contact with Marcel Duchamp and Alfonso Ossorio. The later showed her his collection of paintings by Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, and Clyfford Still, abstract artists Bingo was influenced by but whom she increasingly separated herself from as her career progressed. And though she participated in the historic GangBang exhibition at the Batman Gallery in San Francisco alongside Rat Bastard artists, and had a solo show curated by Conner in 1961, she is not featured in any of the recent scholarship on the Rat Bastards. Perhaps that is because Bing, who is described in the Worlds of Bernice Bing film as a “wild butch, smoking Shermans and drinking brandy,” was frequenting North Beach’s burgeoning queer community and underground lesbian bars, rather than hanging out in the many well-documented countercultural art hubs.

Bing’s outsiderness, based on a combination of geography and biography, is very apparent in this show. We learn that in 1963, Bing took a job as a caretaker at Mayacamas Ranch, a retreat in Sonoma County where she shifted her practice to landscape. In 1967 she was admitted to the first residential program at Esalen in Big Sur, where she studied New Age psychology and philosophy with the likes of Allan Watts, Joseph Campbell and R.D Laing; there, she was also influenced by Zen Buddhism’s practice of releasing the ego and contemplating nature, evidenced in visionary works such as Big Sur (1967), which is described in the show’s catalogue as “a notable autobiographical work as an apparent representation, if not reconciliation, of her lifelong effort to balance the cultures of East and West.” The painting, with its curved mountain forms intersecting a strong horizon line with what appears to be a floating figure in the sky recalls compositions by 19th-century symbolist painters Odilon Redon or Gustave Moreau. During the 1970s, Bing’s little-documented visionary work appeared intermittently but was included in Carlos Villa’s seminal show Other Sources: An American

Big Bingo Games

Essay at SFAI (a 1976 study of the cultural diversity of the city’s art scene). We also learn that at this time she was an enthusiastic and impactful activist for her Chinatown neighborhood association and for the California Arts Council; by the early 1980s, Bing was appointed director of the South of Market Cultural Center (SOMArts).

Nineteen-eighty-four was a watershed year. Bing traveled to Korea, Japan and China where she studied calligraphy and lectured on Abstract Expressionism to art students. At the China Academy of Art in Hangzhou, she worked with Wan Dongling, an artist known for merging Western and Eastern aesthetics. It was during this trip that she may have filled in the cultural omissions and discontinuities that came from being a Chinese orphan raised in almost entirely Western environments in California. When Bing returned, she moved to the town of Philo in Mendocino County, where she focused solely on painting and spiritual practices until her death in 1998. The catalog authors argue that Bing’s lifelong work of reconciling her Eastern heritage and Western training into a uniquely intercultural language culminated during her years in Philo. There, Bing created such pieces as Abstract Calligraphy (1987) and Vital Energy

(1986), engaging in a dynamic, elegant fusion of calligraphic practice and abstraction, defined by a recognizable line and a deeply personal Abstract Expressionist language. But why Philo? Why abandon arts activism in the city? Was she seeking a community she could not find elsewhere? Was her health precarious? Did this self-imposed exile further marginalize her from the artworld? The Life and Art of Bernice Bing may recuperate her work and biography as a fusion of her Asian and Western heritage and promote her universalist painting process as sui generis, but like any successful retrospective, it leaves us wanting more.

Bingo Bingo Bingo

For a memorial speech in honor of her friend Bingo at the San Francisco Art Institute on September 26, 1998, feminist critic Moira Roth drew from her journal, dated July 30, 1998: “Talk with Bernice over tea this morning—she is more and more deeply drawn to Tibetan Buddhism, up until now she says that she has been involved with a more outer-directed form of Buddhism, with the focus on peace and social justice. The Tibetan version is more inner-directed—she uses the word ‘clarity’ to apply both to its practice and the goal she has set herself for her new paintings.” Bingo: The Life and Art of Bernice Bing reminds us of the strange and wonderful ways art history shapes itself across time, place, and the lives of individuals, and tells Bing’s story as it has yet to be told. Even so, Bing’s art and life remain mysterious to us and in another O—obscurity.

# # #

Bingo: The Life and Art of Bernice Bing @ Sonoma Valley Museum of Art through January 5, 2020.

About the author:

Natasha Boas Ph.D. is an independent scholar and international curator based in San Francisco and Paris. Boas was trained in the modernist avant-garde, and now specializes in counterculture artists and women artists. Most recently, Boas curated the first US exhibition of Algerian-born artist Baya Mahieddine (1931-1998) Baya: Woman of Algiers at NYU Grey Art Gallery to critical acclaim. Like Bing, Baya was a forgotten trans-cultural artist whose contribution to the modernist canon is just now being recognized.